All throughout childhood, we can’t wait to grow up. But now that we’re of adult-age, why does it seem so hard to fully embrace adulthood?

Here’s a confession from your fellow Gen Yer: despite having been an adult for six years, sometimes I still feel like I’m a fraud. I’ve always thought that being an adult, I would dress better. I would have deep and meaningful chats with friends and acquaintances every time we have Italian dinner. I would walk pass the salespeople on the street and politely look them in the eye and say, ‘No.’

At the very least, I thought I would be able to go to the liquor store and buy a six-pack without getting asked for ID.

Some weeks ago, after having dinner with a friend, we stopped by the supermarket and I was thinking to pamper myself with a bottle. I marched as per usual to the counter, and the Caucasian lady in her late 40s took one look at me and asked for my age identification.

‘Seriously?’ I asked.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I can’t sell this to you otherwise.’

I put my ID out but she didn’t recognise my Indonesian driver’s license nor my national identity card. I proceeded to search for a print screen of my passport on my phone, while two minutes too long later she said, ‘I can’t sell you this if I don’t see the physical passport.’

Well, seriously, she should have told me that sooner.

So it’s not only me who feels like I’m not yet an adult. Even a supermarket clerk feels like I’m too young for having beer on a Thursday night. Guess what? I’m turning twenty-four.

Sure, society states that there is a checklist—a series of things—that makes you feel like an adult. Paying for your own bills, for example. Moving out of your parents’ house. Getting a steady paycheck. Saying I do. Having kids. Buying a house. And other things that I’ve not yet done (except for paying the bills, I guess).

Adulthood is, in my humblest opinion, hard. I’m still freaking out about what I’ll do after graduation in four months’ time—whether I’ll actually be able to get a job and hold it for the next two years. I’m freaking out about what will happen next—what about mortgage, children, a lack of friends? What about loneliness? What about friends-who-are-just-too-successful-and-I’m-ashamed-to-say-that-I-used-to-be-on-the-same-ladder-as-them? What about money?

The term ‘adult’ means, according to the Macquarie Concise Dictionary:

a person who has reached the age, variously defined in different political systems and legal contexts, at which an individual is considered to be fully legally responsible and can assume certain civic duties, such as voting (in Australia, the age of 18)

But we all know too well that age is just a number—having that license in your wallet and being able to order a glass of wine at the restaurant don’t magically transform you into an adult.

Culture and society often dictate when a person can rightfully be seen as an adult. Some even have their own ‘rites of passage’ to adulthood, marked by certain ceremonies. If you were Jewish, you’d probably be having Bat Mitzvah when you were 12, showing your commitment in Jewish tradition and law. If you were Japanese, you would be dressing in your finest traditional attire when you were 20, attending the annual Coming of Age Festival (Seijin-no-Hi) on the second Monday of January. If you adopt the Western culture, you’d be celebrating your Sweet Sixteenth birthday, hopefully not getting too drunk by the end of the night.

And coming-of-age is a topic that’s being documented too well in the media nowadays. Even the iconic Disney movie The Lion King (and every other Disney movie) talks about how one teenager grows up to become an adult. Simba becomes a lion, and no longer a cub, when he realise that Hakuna Matata (it means ‘no worries’) is not the right motto, but ‘the past can hurt. But the way I see it, you can either run from it, or learn from it’ is.

Katniss from The Hunger Games stops being a child rather early—at the age of 11, in fact—when her father died in a mine explosion and she has to take care of her family as her mother goes through depression.

Harry Potter becomes an adult, in my opinion, either at the fourth book when he witnessed Cedric Diggory’s murder or at the sixth book when Dumbledore died. (Ahem, the recurring theme seems that the death of a loved one triggers whatever childhood-like character we have left into adulthood.) Of course, we can debate about this all day, and we’ll still not come to agreement.

But we all know too well that age is just a number—having that license in your wallet and being able to order a glass of wine at the restaurant don’t magically transform you into an adult.

Yet our current generation loathes being an adult. Pew Research Center in the US runs a survey to 1821 adults ranging in age from 18 to 33 in 2014, which is called ‘Millennials in Adulthood‘. What they have found about our generation is this: We are confident, connected (digitally) and flexible of life changes even in the face of adversity. We are less religious compared to our parents’ generation, and even when the economy keeps on getting worse, we are actually the optimists, believing that things will turn out okay in the end.

Yet we are delayed in maturing—not marrying, having children, buying a house or moving out of our parents’ house being the contributing factors.

With the shift in lifestyle, our culture changes too. In 2011, Dan Weiss, the Publisher-at-Large for St. Martin’s Press, created a new category of readers: New Adult. This is the term to describe a large number of adults who read young adult (YA) books, also known as the ‘easy books’.

There is a lot of controversy surrounding this, and one very famous article by journalist and critic Ruth Graham goes as far as saying that those who read YA books ‘should be embarrassed when what you’re reading was written for children’. People should be reading Hemingway, and not John Green.

Perhaps Britney Spears know it best when she sings, ‘I’m not a girl, not yet a woman.’

So the current generation is delaying adulthood. We move from our parents’ house later (blame the economic recession), get married later and have children later.

Instead, we are obsessed with YA books and video games (think about the four very adult scientists in The Big Bang Theory) and lied to our boss that we are attending a funeral back home but building a tree house instead (yes, one millennial did do this). The dictionary seems to be needing an update, as psychologists now define the upper limit of adolescence not at 18, but 25.

There’s even a new term for it: ‘emerging adulthood’, coined by Developmental Psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett in 2000, showing that ‘a new concept of development’ is needed to describe the period from late teens through the twenties, or basically, the 18–25 age group. Current adults, it seems, are facing the failure to launch.

Perhaps Britney Spears know it best when she sings, ‘I’m not a girl, not yet a woman.’

So here’s the question of the millennium: When can you call yourself an adult? Legally, of course, you can say you’re an adult when you’re 18, although this depends on which country you’re born. Is it when you become financially independent? When you get married and start having kids? Or is it when you flip the switch somewhere in your brain and say, ‘Yes, from now on, I’m an adult’?

There’s power in voice, so I decided to ask fellow friends, acquaintances and ex-colleagues alike about what they think being an adult really means.

I sent out three (or if you want to be exact, five) questions: What, in your opinion, being an adult really means? Do you consider yourself an adult? When did you first consider yourself an adult? Or if you haven’t, why? Anything else you’d like to add?

I was expecting to get a three-sentence answer, but in reality, many reply with a one-page essay. Several of them say, ‘Give me some time to think about these deep questions.’ All in all, I have gotten over 60 replies with over 16,000 words of cumulated answer. Stop and ponder what that means for a while.

When can you call yourself an adult? Is it when you become financially independent? When you get married and start having kids? Or is it when you flip the switch somewhere in your brain and say, ‘Yes, from now on, I’m an adult’?

I do my best in trying to get people from various walks of life to share their two cents. If you’re a statistician, I’d like to tell you that my dataset includes roughly equal number of both genders aged 20 to 47, with a median of 25 (I have two outliers of people in their 40s, but moving on). I am very overwhelmed (in a positive way) by their answers.

And to give you the ending up front: There’s no straightforward answer. I’ve included some of their responses here, and you can read the full answers at your own time.

I think there are a lot of aspects to consider about being an adult. I think it’s a mixture of being financially independent (having a career) and balancing every other aspect of your life alongside it. Learning how to prioritise your schedule is a major factor, be it ensuring you meet job/uni deadlines to making sure you’re feeding yourself three meals a day – healthy meals at that.

Overall, I think I do [consider myself an adult], but only to an extent … I think I’ll only fully consider myself as an adult when I have a proper career and when I can confidently put down the first payment on a house.

I think there are so many expectations of you when you hit your mid-twenties. You scroll down your Facebook timeline and you see friends (around the same age as you) getting engaged/married, studying, kicking off their careers, travelling the world etc, and you can’t help but compare and question yourself: ‘Am I doing okay for my age? Or am I lagging behind everyone else?’

– Amy, 24, Masters Student in Teaching

Adulthood, everyone agrees, is defined by several keywords: maturity, independence and responsibility. It seems that the first hurdle of adulthood is getting that constant paycheck and gaining financial freedom from our parents.

To most people, this happens around the age of 22, or after they graduate from universities and hold their first full-time jobs. Others hit the flip-switch when they have children. To others, however, the concept of adulthood is more complex.

Half of my responders say that they feel like they are kidults (and yes, the term is actually there in the Urban Dictionary), even when they are well into their 20s or even reach their 30s. Most of those in this category feels that way because they are not yet a hundred per cent independent from their parents, but for others, paying the mortgage and earning more than enough money don’t seem to do the trick, as they haven’t scored on other adult–life stages, such as in relationship.

Yet some who are both financially independent and married don’t think that they are adults either.

(Fun fact: Those who somewhat consider themselves as adults tend to give me much longer answer.)

I never really feel I am an adult, I just feel I grow in maturity. I can handle problems and responsibilities not by throwing tantrums or putting blames but find a way to solve it. Maybe because I still feel my parents are the adults here even after I get married. I just feel I am growing older and a bit wiser I guess, but I won’t say I am an adult.

– Sartika, 30, Graphic Designer

Even at the age of 24, oftentimes I don’t consider myself as an adult. I am still in the process of finding myself and sometimes I don’t have clear priorities. Although I’m working, I’m still financially dependent on my parents. Crucial decisions that I made are with interventions from my parents.

– Emma, 24, Financial Analyst

So perhaps adulthood can’t be simply marked by turning a certain age, being financially independent, getting married or having children. Perhaps the answer is more elusive than that. Some suggest that adulthood is a journey, and it’s relative. There’s no one right way of being an adult, as everyone has different life experience.

I started to consider myself an adult when I stopped relying on my parents for money completely, when I tell them my travel plans and career plans not to seek for their permissions but just as a courtesy, and when I get more excited buying them presents than getting one from them.

– Beatrice, 23, Software Developer

Yes [I consider myself an adult], but I don’t think being an adult is a milestone, it is more of a journey. For me, it started when I realise that I would rather compromise or give up my own comfort (time, energy and money) to ensure others’ well-being is taken care of.

– HG, 31, Management Consultant

I consider myself a young adult – kind of in between a young person and an adult. I think adulthood is relative. For me, the transition to adulthood has been gradual. I didn’t wake up one day feeling like I’ve transitioned from a teenager into an adult. There was never really any point in time where I felt like I switched into an ‘adult’. Turning 18 legally made me an adult but for me it was just like any other birthday. There is not ‘right’ pathway to adulthood. Everyone’s journey is different.

– Tim, 24, Communications

In trying to attach an answer to the question, I come to ponder on my own motive on writing about adulthood. It’s no secret that I’m turning twenty-four, and that I’ve recently become engaged. Perhaps it’s my own way to understand myself in a better way.

And yet the Psychology student in me pesters that there is something more—that in the core of all these there’s something important that needs to get out there. While thinking on that, I come to another question: Is it important for me to be looked as an adult?

As a child, I’ve always wanted to be a grown-up. And there are no better grown-ups than my parents, who become the epitome of my definition of adulthood.

Do you find it important to be looked as an adult?

Mom got married when she was my age and had my sister one year after. She wakes up before dawn and prays for us for an hour before going down to the kitchen to make breakfast, then waking me up to prepare for school. She always gives us the best part of the chicken during dinner, and asks what we want to have for lunch the following day.

Dad is the provider of the family. He goes to work, comes home and eats dinner with us, and shares his stories from childhood after dinner. He listens to my troubles, and one day when I came crying to him for a boy was bullying me, he went home early from work to pick me up from school and become my knight in shining armour. Suffice to say that I was smiling ear to ear on the car ride home.

Being adults doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes, because they do. But even when they do the wrong things, it seems like they do them with the right intentions.

Mom, for example, always reprimands me by commenting on how ‘when your sisters were your age, they were not doing this and that’. Her intention is right: to make me a better person. But her way of doing it is wrong, as I don’t like to be compared to my perfect sisters. (I’ve argued my case on being the youngest child elsewhere.)

It’s like what Po’s father, the Goose, says in Kung Fu Panda 3, ‘Sometimes we do the wrong things for the right reasons.’

Being adults doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes, because they do. But even when they do the wrong things, it seems like they do them with the right intentions.

But when the adult-me makes mistakes, she does them with the wrong intentions.

Just last week, I got mad at my fiancée for looking intently at his newly washed car for seven minutes, as we were going to watch a movie that would be playing soon. We sat down in the cinema, and while the movie trailers were playing, he said, ‘You have to learn to compromise.’

‘But I don’t understand why you need to look at your car for far too long,’ I said, visibly showing my anger. ‘You know that we’re going to watch a movie. It’s not that important.’

‘The thing is,’ he said, ‘it’s important for me.’

We let it slide and I almost said I was sorry for being such a pain, but I didn’t. So in that case, I assume I wasn’t being an adult.

But then again, perhaps that incident captures what being an adult is all about.

Being an adult doesn’t meant that you have everything figured out.

I’d like to think that adulthood is not a flip-a-switch thing, and more of a process. You call yourself an adult and act like one, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t make mistakes.

Simba, well into his role in parenthood, acts like a child in The Lion King II, intervening in his adult daughter’s life too many times. Katniss cries in self despair too much in the first half of Mockingjay. Harry ought to know better than fighting with his best friend Ron in the Deathly Hallows.

Being an adult doesn’t meant that you have everything figured out.

I bet our parents don’t know what they are doing half of the time—as babies and teenagers don’t come with manuals—they are just getting better in simply doing it. Adults are adults because they don’t only take care of themselves, they take care of others.

That’s why the switch often happens in parenthood, as we become people who are looked upon instead of merely looking up to others.

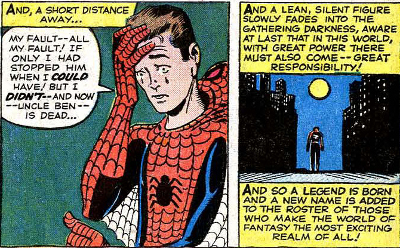

And with that kind of power comes great responsibility.

Over time, I’d like to think that we get to become adults when we are not trying that hard in putting in the definition ourselves. Author Jeff Goins says, ‘You are a writer when you say you are.’ Perhaps it’s the same with being an adult.

Some holidays ago, I was back at my hometown, Jakarta. My parents and I were in the car going for lunch, and Dad suddenly said, ‘Ella seems more mature now. She is not easily angered anymore, even when plans get changed. She has become less selfish.’

I sat at the back seat of the car, pondering on what Dad just said. I hadn’t realised the change. I still woke up late and spent the first half of the morning in my pyjamas while doing work. I still left dishes on the sink, sometimes for days. But something has changed inside me, and my Dad, the quintessence of my definition of adulthood, acknowledged it before I did.

Over time, I’d like to think that we get to become adults, when we are not trying that hard in putting in the definition ourselves.

In the wise words of C.S. Lewis:

Critics who treat ‘adult’ as a term of approval, instead of as a merely descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown up because it is grown up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these things are the marks of childhood and adolescence.

And in childhood and adolescence they are, in moderation, healthy symptoms. Young things ought to want to grow. But to carry on into middle life or even into early manhood this concern about being adult is a mark of really arrested development.

When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.

Being an adult means a lot of things. It means being of a certain age, but not completely. Social norms, such as being financially independent and getting married, are markers of adulthood, but they don’t constitute the definite checklist. Being mature and putting others above ourselves are just concepts, but they do not paint the whole story. The definition of adulthood differs for one person to another, and in a generation that constantly looks for others’ attention, appreciation and acknowledgment, perhaps adulthood is simple.

Being an adult is a choice—it simply is.

Photos are used under Creative Commons Zero license, in exception of the section of Spider-Man! comic. Published 1962, Writer: Stan Lee, Illustrator: Steve Ditko, Marvel Comics, New York. Credit: Quote Investigator.